I have my father’s datebooks-turned diaries dating back to 1969, and gradually started reading them in the summer after he died. One of the names that came up, after hushed-tone warnings of my mother’s that “he was dating a man,” was Edwin Bayrd’s.

For whatever reason I never managed to track him down after Googling his name every now and then, but I got to read about their relationship for some years in the early 70s through the diaries.

Edwin wrote me quite out of the blue via my website in December of 2021, and offered to share his stories and recollections. After explaining that I knew of their relationship and the meaningful person he was in my dad’s, I was happy to read his fuller “unedited” version of these recollections.

Copied below is a short fragment from those email exchanges, and the full text of the chapter “Walk on the Wild Side” from his upcoming memoir, one chapter of which recounts the relationship they had together.

… As far as I know, I am the only man your father had a romantic relationship with—and I hasten to add that our relationship began with fond mutual feeling, from which the rest followed… I was only just coming to terms with what is now referred to as my “sexual preference.” And your father was in thrall to David Bowie, Lou Reed, and the whole notion of fluid sexual identity. There was nothing androgynous about your father; he was a hyper-masculine force, as you are well aware. But he enjoyed playing with gender expectations… and taunting the prudes.

I think his whole life was, in a way, a flight from all expectations. He was, like me, an old-line WASP with an Ivy education. Unlike me, he was an All-Ivy tackle who won a Thuron scholarship to study economics in Edinburgh. The perfect resume for a young man bent on a career in business or banking. But then something happened while he was in Scotland: he turned his back on those rosy prospects, moved to London, and enrolled at RADA. The rest, as they say, is history.

I have recorded some of that history in a volume of personal reminiscences that I wrote this year. It is titled My Life in 17 Songs, and each section is pegged to a song that evokes a particular phase of my life.

Below is the “Song” about Henry:

“Walk on the Wild Side,” Lou Reed, 1972. I am 28.

In a sense, writing Kyoto, Japan’s Ancient Capital for Newsweek Books’ Wonders of Man series was a meal eaten in reverse: first the dessert, which was the time I got to spend in Japan; then a great helping of spinach, which was drafting the text itself. This large helping of steamed greens included many long hours spent in the cavernous central reading room of New York City’s main library, the splendid Carrère and Hastings Beaux-Arts building located at Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street.

Writing is a solitary occupation, and to alleviate my solitude I enrolled in a course in introductory Japanese at the Japan Society, which is on East 47th Street in New York City, mere blocks from the United Nations. In part, I wanted some human interaction, but I was also motivated by a growing sense of embarrassment: I had been engaged to write a cultural history of pre-modern Japan… and I did not know more than a few words of the Japanese language.

It was apparent to me even then that one cannot really come to know another culture without knowing its language—and that is particularly true of Japan. To cite but one example, the Japanese have nine different words for wife. The most common of these is oku-san, and it can be used to refer to anyone’s wife. When a man uses kanai, he can only be referring to his own spouse, because the word is inherently demeaning. When used to refer to one’s own wife, it suggests an appropriate degree of humility; one doesn’t boast about one’s helpmeet. When used to refer to another’s wife, however, the term would be implicitly insulting—suggesting that she was little more than a kitchen drudge.

The class I enrolled in at the Japan Society was taught by Fumie Adachi, who was a tiny sparrow of a woman with an indomitable spirit and a sly wit. Just how indomitable she was I would learn much later. It turned out that she was the daughter of a Kazoku baron, the lowest order of hereditary peerage in Japan. As such, she was considered a very desirable match for a young man with social, political, or economic ambitions.

A match was therefore made, in traditional Japanese fashion—through the families of the prospective bride and groom—and only then was this omi-ai union announced to the bridal pair. The practice of arranged marriage, once nearly universal among upper-class Japanese, still persists. To the consternation—and the humiliation—of young Fumie’s family, she refused to marry the man who had been selected to be her husband… and when her father ordered her to submit, she fled to America, learned perfect English, and supported herself by teaching classes at the Japan society to gaijin—foreigners—like me.

My class was filled, in the main, with businessmen who were going to be dispatched to their corporation’s Tokyo offices… and who had been instructed to acquire at least a rudimentary understanding of Japanese before they left the States. To a man, they imagined that they could achieve this end through osmosis: they dutifully showed up, every Tuesday evening, but they never did a lick of homework and they knew no more Japanese when they finished the 10-week course than they did on the night we convened for the first time.

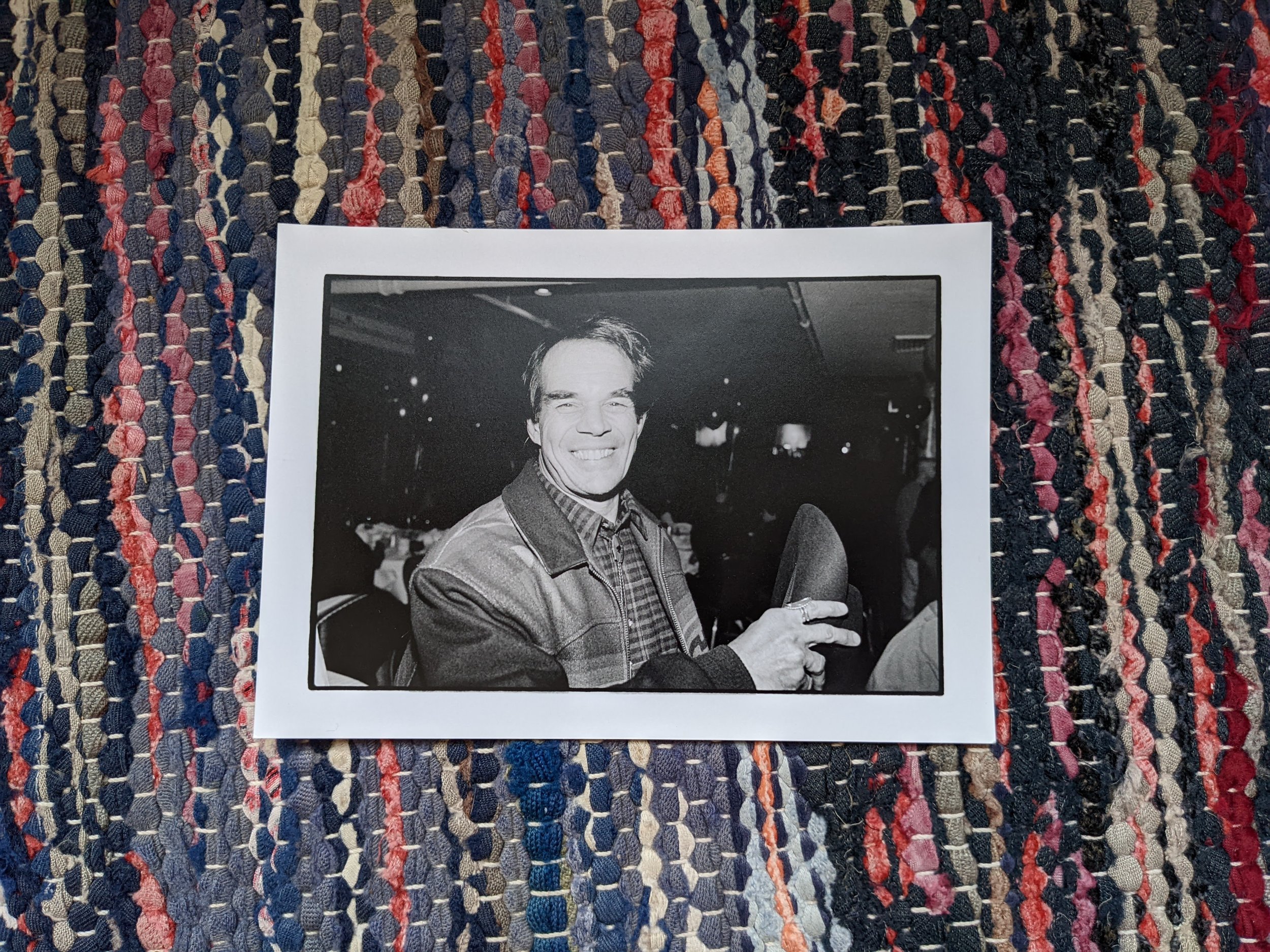

Only two of Miss Adachi’s students applied themselves. One was me, and the other was the madman who seated himself across the table from me on that first night. He had a line-backer’s body, a large surgical bandage across the bridge of his nose, and the eyes of a cornered beast.

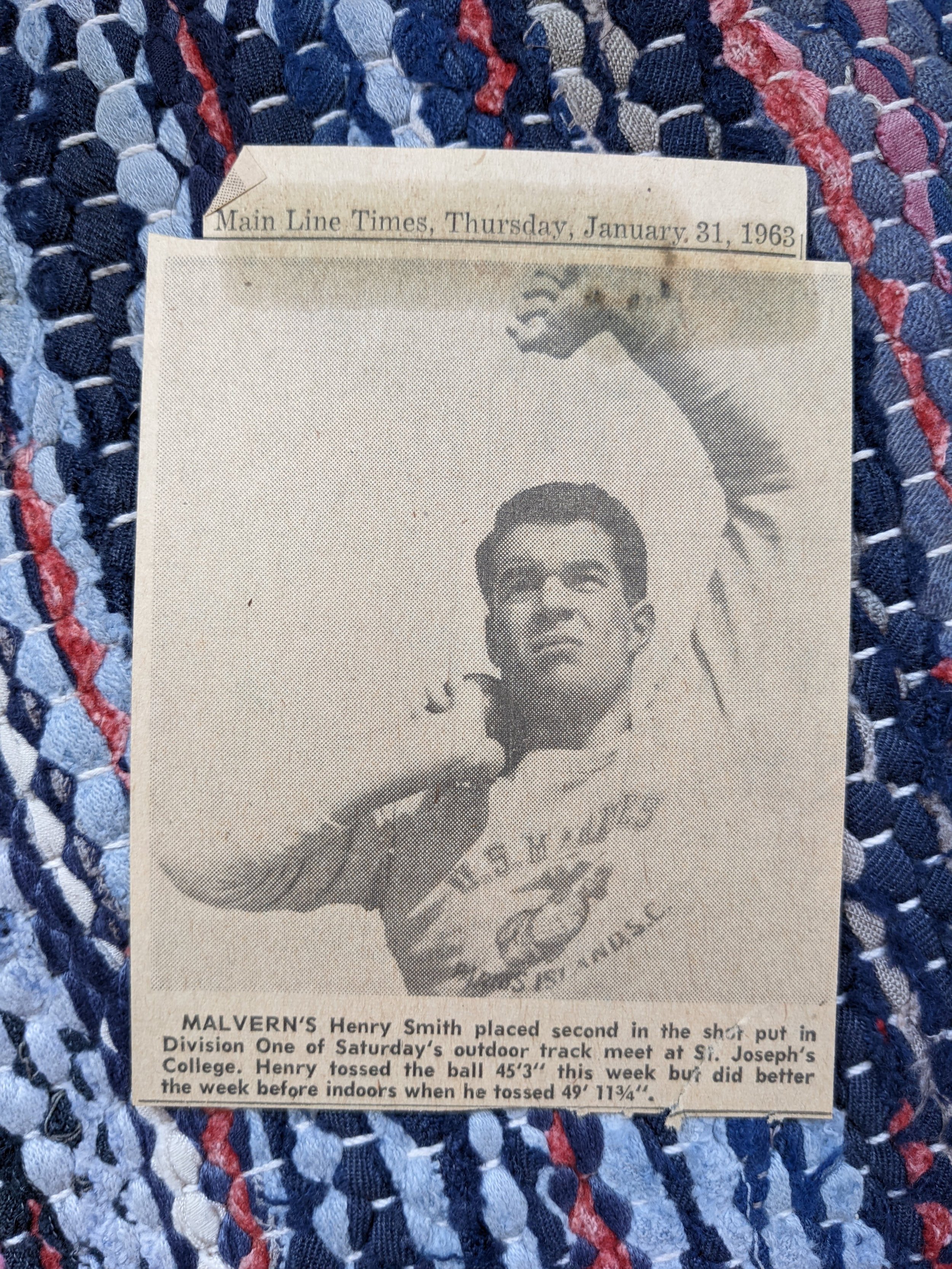

His name was Henry Clay Smith III, and as I would learn over the ensuing weeks, he came from Philadelphia’s Main Line, which made him every bit as much of and old-line WASP as I am. His broad shoulders reflected his years as an All-Ivy tackle on the Penn football team, and the bandage he was wearing on the night we met covered a recent effort to repair a septum that was so badly deviated, after repeated blows on the football field, that Henry could barely breathe through his right nostril.

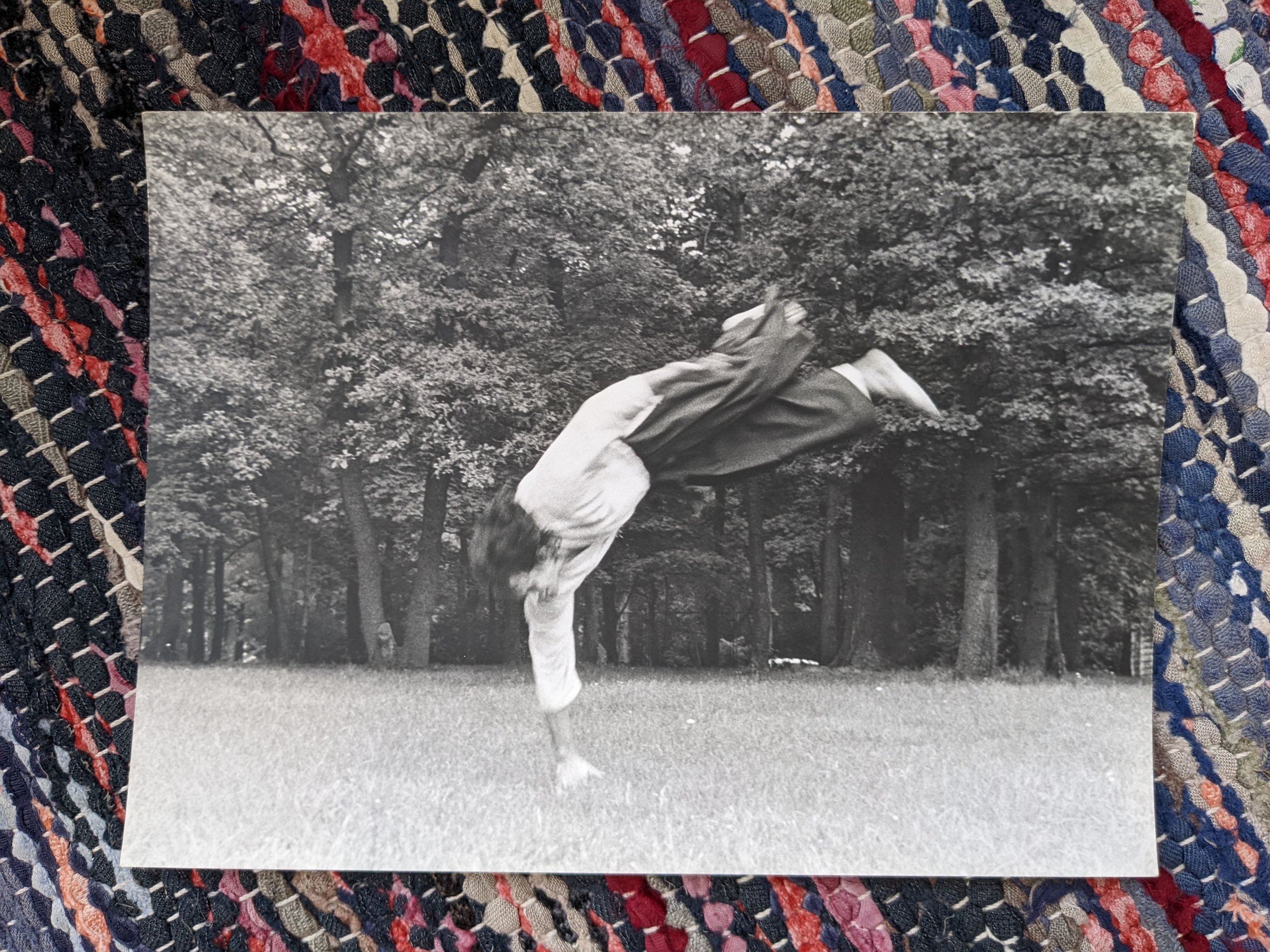

All this fits with Henry’s background and his career as an Ivy League athlete. So does the fact that he won a Thouron Award, Penn’s equivalent of a Rhodes scholarship, which took him to Edinburgh for two years of postgraduate study. And it follows logically that while this ex-footballer was living in Scotland he would get involved in the Highland Games. His specialty was the caber toss.

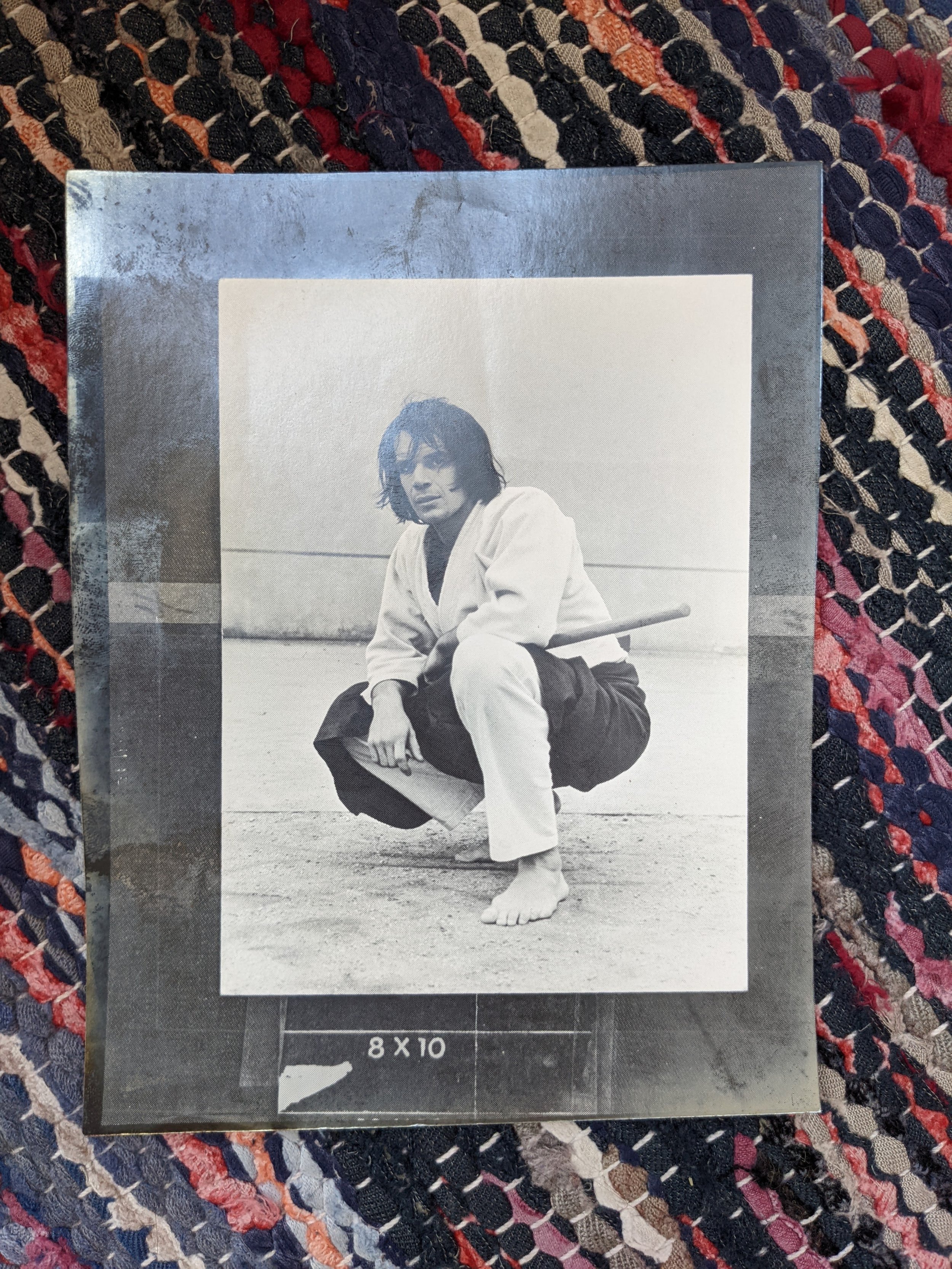

Somewhere along the way Henry took up aikido, a ritualized Japanese martial art whose primary goal, as articulated by the founder of the discipline, was to “overcome oneself instead of cultivating violence or aggressiveness.” Well, perhaps—although in Henry’s case I suspect the purpose of attending aikido dojos was to sublimate his own aggressive tendencies and channel his innate restlessness into choreographed action. It was his commitment to Japanese martial arts, including the ancient art of combat with jo sticks—a particularly good example of choreographed action—that brought Henry to Miss Adachi’s evening course at the Japan Society. Like me, he realized that you cannot really appreciate a culture unless you understand its language.

What comes next does not follow logically. Indeed, it is every bit as unexpected, and norm-shattering, as Fumie Adachi’s decision to flee Japan, her father’s wrath, and her fate as an omi-ai bride… because when Henry’s Thouron stipend ran out, he moved to London instead of returning to the States. He enrolled in RADA, as the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art is known, and took acting classes. During this period he won the lead in a local production of Fortune and Men’s Eyes, a well-reviewed and well-received play but one that was, for its time, an unusually explicit examination of homosexual activity and sexual slavery in prison.

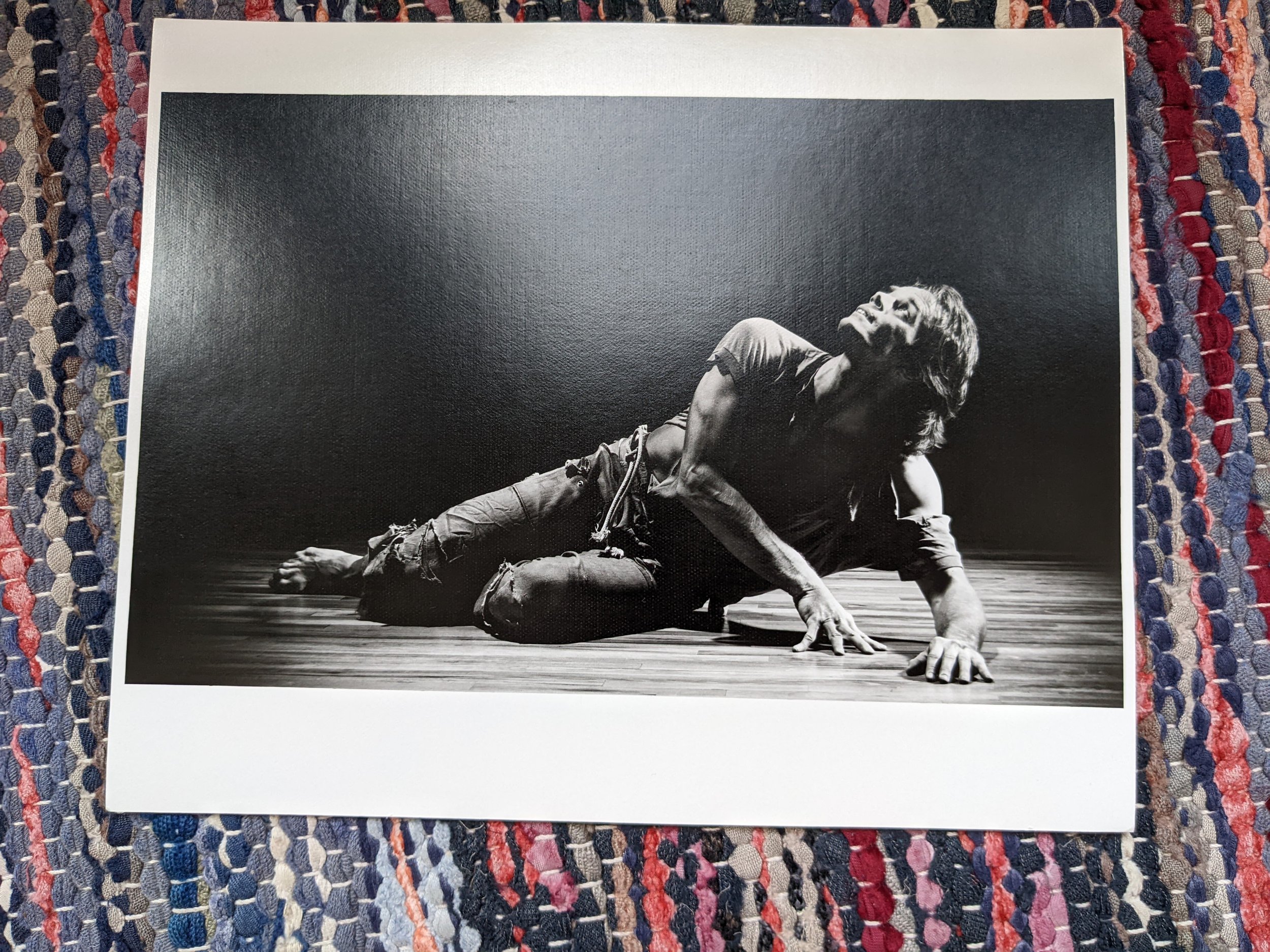

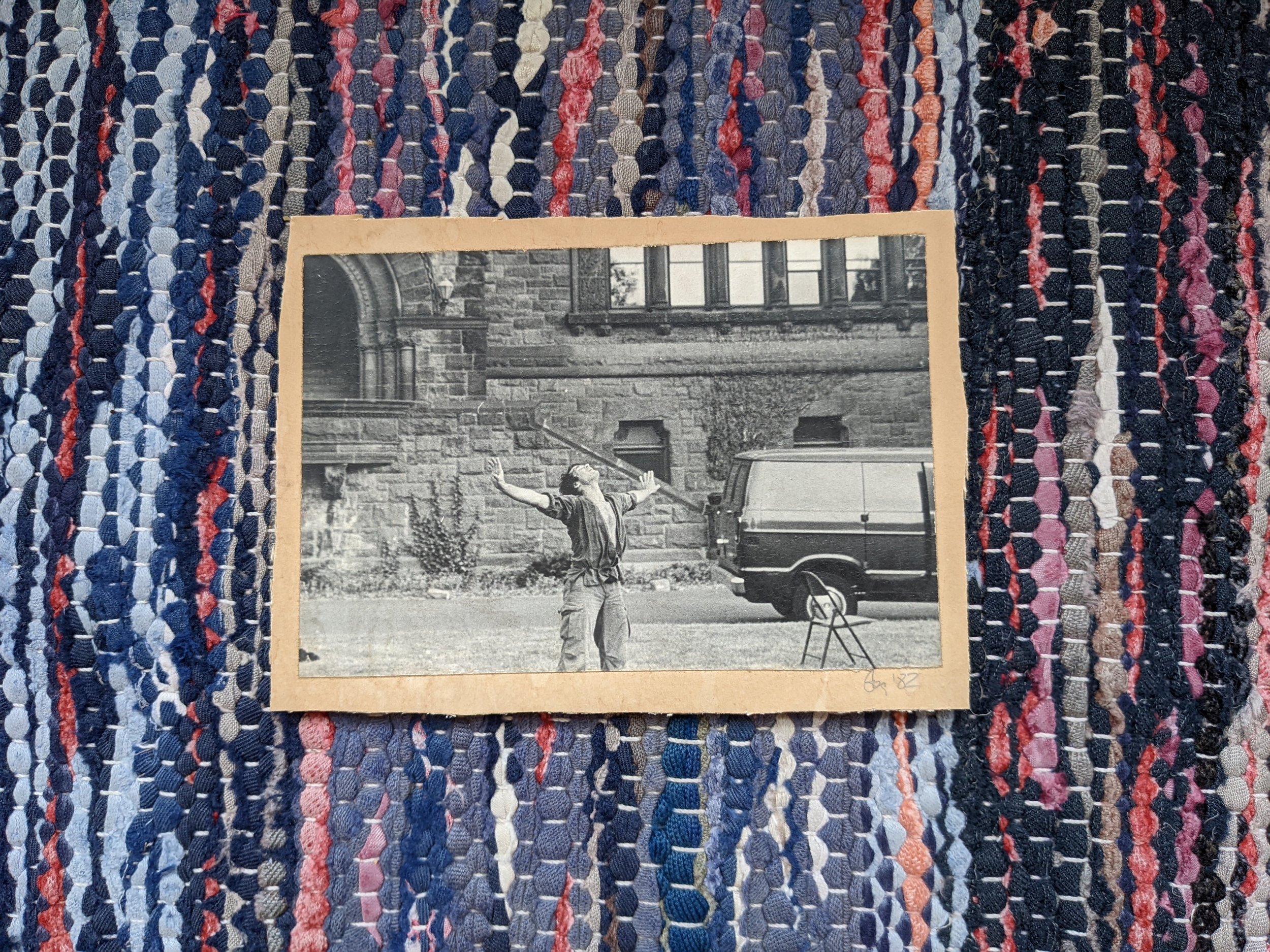

Henry’s transformation from bruising left tackle to mesmerizing stage performer did not end there, however. He next enrolled in dance classes, and at the time I met him he had just returned from Paris, where he had collaborated with Carolyn Carlson, an etoile of the Paris Opéra Ballet and Rudolf Nureyev’s frequent partner. In order to keep this star ballerina from defecting to another ballet company, the director of the Opéra acceded to Carolyn’s wish to form an experimental dance-theater company under the auspices of the opera house. It was this group that Henry, by now a slimmed-down football player but by no means a sylph, joined.

With unassailable logic, Carolyn cast him as the Minotaur in her first production. Not long thereafter, another modern-dance choreographer, Anna Sokolow, who began her career as a soloist in Martha Graham’s original company, would use Henry in a similar fashion, in her one of her best-remembered pieces, “The Rope.” Sokolow created the solo on herself in 1946. In the 1970s she gave it, in perpetuity, to Henry, in recognition of the animal magnetism and theatrical force of his interpretation.

It turned out that Henry and I lived some twenty blocks apart on Eighth Avenue: he, at 19th Street in Chelsea; I, at Barrow Street in the West Village. We made this discovery by finding ourselves on the 53rd Street platform of the downtown E train, after our first class at the Japan Society. Both of us were waiting for the same train to take us home… and once we made this discovery, we made a point of walking up to 53rd Street together, and taking the E train to the station at 14th Street and Eighth Avenue. There we would part company: I walked south to Barrow Street; Henry walked north to his fifth-floor walk-up on 19th Street.

At the weeks went by, we found ourselves lingering longer and longer at 14th and Eighth, without being altogether certain why. Neither of us proposed, say, going somewhere for a cup of coffee or a drink, but both of us recognized, at some level, a growing reluctance to say goodnight. And then, one snowy November night, with soft flakes floating down on us through the amber light of the streetlamps, Henry turned to head uptown, turned back, and kissed me on the lips.

My orderly world was upended in that moment… and in a very short time I was swept up in the maelstrom that was Henry’s life. He was as daring as I was cautious, and he was as heedless of society’s expectations as I was mindful of them. The word that would be used today to characterize Henry’s headlong rush through life—and his eagerness, his insistence, on challenging conventional morality and social norms—is transgressive.

And transgress he certainly did. After a performance at the Opéra, the other members of Carolyn Carlson’s troupe carefully removed their stage makeup—but not Henry. And so, when the troupe retreated en masse to the Cupole or Select for a post-performance meal consisting mostly of Gitanes and wine, Henry was the only one to show up in highly theatrical maquillage; mascara, eye-liner and, more often than not, rouge. To heighten an effect that needed no heightening, Henry frequently added a long, gauzy scarf. On one of the other male dancers this sort of flamboyant public display—the very definition of épater les bourgeois—might have elicited homophobic slurs… but Henry was so physically imposing, and so clearly indifferent to what strangers thought of him, that he provoked stares, but no taunting jeers of quel pédé or quelle tapette.

I observed this behavior first-hand, on the several forays I made to Paris—with almost no French and almost no money—to watch Carolyn Carlson’s company perform. On one of these occasions I arrived in Paris unannounced, intending to surprise Henry in the green room of the Opéra after the company’s performance. Upon my arrival I discovered that Carolyn’s troupe was scheduled to perform not at the Palais Garnier, as the magnificent Paris opera house is known, but at an auditorium in La Défense, a planned city, then less than two decades old, on the western outskirts of metropolitan Paris. The piece, I read, was called “Relâche.” It took me more than an hour, with the help of my well-thumbed Taride, a street and subway map of greater Paris, to make my way to that distant venue… where I learned that relâche is the term, in theatrical circles, for “performance cancelled.”

For the most part, I was a mere observer of Henry’s antics, but on one particular night in Paris I was an active participant in Henry’s tweaking of bourgeois noses. He and I were strolling back to our Left Bank hotel, an establishment so seedy and cost-conscious that you had to hit the light switch in the lobby and then race up the first flight of stairs before a timer on the light plunged you into darkness. You then had to repeat this process on successive floors, until you reached your garret room in the elevator-less building… where an astonishingly lumpy bed, which sagged in the middle and rose sharply at both ends, awaited you.

As we passed Les Deux Magots, where Hemingway used to drink and where I once heard Maggie Smith berate her husband in her very distinctive voice and in very unladylike language, Henry came to a full stop. “I’m going to go in,” he said. “You wait outside for ten minutes, then come in… and pick me up.” As instructed, I cooled my heels on the pavement for what seemed like an hour, entered the legendary brasserie, took a stool at the opposite end of the bar from where Henry had positioned himself… and then made a great show of staring at him, acknowledging his response, giving him the broadest of winks, and sending him a drink. Henry saluted me with the beer stein when it arrived, turned to face me, groped his crotch, sauntered to my end of the bar, and nuzzled my neck. By the time he and I walked out together, the room was utterly silent.

Groupie that I was in those days, I even drove down to Avignon to watch Henry and the rest of the dancers perform at that city’s legendary summer festival. In retrospect, I am not at all certain how I managed any of that, but somehow I persuaded Hertz to rent me a small white Peugeot—in which Henry and I somehow managed to get to Avignon by way of Annecy, in the shadow of Mont Blanc. Henry was intent upon participating in a two-day aikido tournament in Annecy before we headed further south, to Avignon, and for this purpose he had brought with him a quilted white cotton jacket, or gi, and the floor-length, deeply pleated, skirt-like pants—known as hakama—that are traditional garb for aikido practitioners.

I spent those two days reading on a long pier that extended out into Lake Annecy itself from the foot of the broad lawn between our hotel and the water’s edge. Henry and I had stumbled upon this hotel quite by accident, and quite late at night—through what I came to think of as Henry’s particular brand of luck. He had not bothered to make a reservation in Annecy, and when we arrived in town, after a five-hour drive down from Paris, we discovered that other, more prudent aikido enthusiasts had reserved every single hotel room in town. Which is how Henry and I found ourselves pushing south along the eastern shore of the lake, stopping at every auberge along the way, in the hope of finding a place to rest our by-now weary heads. We got the same response everywhere that we inquired: “Désolé, monsieur, nous sommes complets”—which is French for no room at the inn.

Eventually we reached Talloires, two thirds of the way down the 10-mile-long lake, where we finally found a hotel that was not complet. Without inquiring about the price, I handed the night manager a credit card and Henry and I were shown to our room It was not until the following night, when we ate dinner on the hotel’s wide veranda overlooking Lake Annecy… and I decided that cheese might be an appropriate way to end an especially pleasant meal… that I came to the sudden realization that we were not staying at just any old country inn—because when the cheese chariot arrived, Henry and I were presented with some fifty different kinds, all displayed a bed of freshly-picked oak leaves. Thanks to Henry’s particular brand of luck, he and I had found our way to L’Auberge du Père Bise, which at the time was one of only a handful of restaurants outside Paris itself that had been awarded two stars by the Guide Michelin.

During the months that I was in New York and Henry was in Paris, we communicated by handwritten letters—quaint, but our only option in the distant days before email and inexpensive overseas telephone calls. Increasingly, Henry pressed me into service as the de facto manager of his non-existent dance-theater company. Like so many talented dancers I have encountered in my life, Henry wanted to make his own work. And like all but one of them, he was not quite up to the task—not that his limits as an artistic director mattered one whit to me, in my besotted state.

“Besotted” is not hyperbole. In one of his mostly-business letters to me, Henry added a marginal note toward the bottom of the very last page: “Rebel, rebel, how could they know? Hot tramp, I love you so.” Those two lines, lifted from a David Bowie song with the same title, were as close as any man would come, for a long time, to telling me what all of us want to hear. Later, Henry would do so less obliquely, but that is how it began.

Roughly a year later, during a tense confrontation about how the proceeds from a recent grant should be allocated, I found myself asking Henry why he put up with me, now that I had been thrust into the roles of nag and nay-sayer. “Because you give me such joy,” he replied. I had those words engraved inside a silver and turquoise ring, which he wore from then on.

What Henry had in mind, insofar as I could gather from his long, discursive letters, most of them written over several days during breaks in his rehearsal schedule, was a next-generation successor to the experimental dance-theater ensemble that Carolyn Carlson had formed at the Paris Opéra and christened with the imposing name of Groupe de Recherches Théâtrales. Henry, for his part, envisioned a kind of Gesamtkunstwerk that would fuse dance, theatre, commissioned music, and spoken text into a coherent, compelling whole… and he charged me to turn his vision into a functioning entity. I had no real idea of how to achieve that goal, but I clearly understood than money would have to be involved, and being, at the time, utterly ignorant of the delicate art—and artful diplomacy—of fund-raising, I did not understand that you start small, with friends and with family-held foundations, and work your way up.

In my blissful ignorance, I sent a grant application off to the only foundation I had heard of, the one established by the Rockefeller dynasty. At the time, Henry was still in Paris and his company did not exist except on paper… and in his head. I was so naïve that I was not surprised when I got a response from one of the senior administrators at the foundation. In retrospect, of course, I am utterly astonished… and frankly abashed at my insouciance. But then, as the saying goes in Manhattan’s garment district, “If you don’t ask, you don’t get.” This was, plainly, another instance of Henry’s particular brand of luck, working through me.

The Rockefeller Foundation next wanted to see the non-existent mission statement of Henry’s non-existent company. I had no idea what a mission statement was, so I asked around. It is, I learned, a succinct summary of why an organization exists and what its objectives are. “When in the course of human events…. “ is a mission statement, albeit not an especially brief one—and, in the world of grant-writing, not a winning one. I was told that the company’s statement needed to be intriguing, distinctive, and compelling—all in the very first sentence. Furthermore, it had to imply that while Henry’s company could certainly use the grant money I had applied for, it would produce dance-theater pieces regardless… and it would eventually be self-sustaining.

I set to work. I submitted a draft mission statement. The grant officer I was working with suggested some revisions that would “enhance” my effort—by which he meant: make it more likely to be funded. I incorporated all of his suggestions… and all of the additional thoughts the grant officer had, when he reviewed my revised draft. At this point Henry returned to New York, and I introduced him to my contact at the Rockefeller Foundation. That was the end of revising my revisions; the grant officer, a discreetly gay man, was as bedazzled by Henry as I had been. The grant application was soon approved… and Henry set to work, finding rehearsal space, auditioning musicians and dancers.

Although I did not appreciate the full value of a Rockefeller grant at the time, I did come to recognize that it was, in effect, the fund-raising equivalent of the Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval. Once Rockefeller had anointed Henry’s vision, how could any lesser foundation say no? Very few of them did, and as a result of my blissful ignorance—and subsequent persistence through a series of guided revisions of his company’s mission statement—Henry was able to find funding for the rest of his career.

Henry’s embrace of life’s inherent contradictions was genuine, and it follows that he would bring that pansexual curiosity with him when he returned to New York in 1972. He was, in many ways, the embodiment of the spirit of David Bowie and other glam-rockers of the period such as Elton John, Freddie Mercury, the New York Dolls, and Iggy Pop. In Henry’s case, the appeal of Bowie’s androgyny was undeniable, although with his prize-fighter’s mug and All-Ivy football player’s physique he hardly looked the part.

It should come as no surprise, then, that Henry insisted I go with him to the Bitter End, the legendary music club on Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village, to hear Lou Reed perform “Walk on the Wild Side.” It is hard to imagine that Reed’s raunchy lyrics could have been be written, recorded, and played on AM radio stations at any time other than the 1970s, an epoch of nation-wide sexual liberation—for women, for gay people, for advocates of what was called free love, for anyone who had been swept up in the 1967 Summer of Love in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury… or had simply responded to the pheromones it had let loose across the country.

Even so I have to assume that most radioland listeners failed to fully grasp that “Walk on the Wild Side” was a kind of primer of sexual subversiveness. I knew who those real-life individuals were; indeed, I had met most of them. And hip Manhattanites also knew who Holly, Candy, Little Joe, and Jackie were: members of Andy Warhol‘s coterie of what he called his “superstars.” Reed’s signature song is, in. fact, a paean to the members of Warhol’s inner circle:

Holly came from Miami, F L A

Hitchhiked her way across the U.S.A.

Plucked her eyebrows on the way

Shaved her legs and then he was a she

She says, “Hey babe, take a walk on the wild side”

Said, “Hey honey, take a walk on the wild side”

Candy came from out on the island

In the backroom she was everybody’s darling

But she never lost her head

Even when she was giving head

“Holly” is Holly Woodlawn, a transgender Puerto Rican actor (“Shaved her legs and then he was a she”). “Candy” is Candy Darling, a transsexual born on Long Island. Reed’s lyrics also mention “Little Joe” Dallesandro, a rent boy and street hustler who came by his nickname legitimately. Although he had the face and figure of a latter-day Adonis, he was only 5’6” tall:

Little Joe never once gave it away

Everybody had to pay and pay

A hustle here and a hustle there….

And then there was Jackie Curtis, a local drag queen who often appeared on stage with her hair dyed a violent red. She routinely wore ripped dresses and stockings, all dusted with glitter… and to both Reed and Warhol she embodied the essence of glam-rock. Who the colored girls are who go “doo, doo-doo, doo-doo, doo-doo-doo” in the loopy, mindless chorus of “Walk on the Wild Side”—they are anyone’s guess.

As we walked westward through the Village after Reed’s concert, Henry asked me if I had any coffee—which he would need to get himself revved up in the morning. Happily, I did… and he spent the night with me for the first time. Hovering over that night, and the all others that followed, are the heartbreakingly wise opening lines of W.H. Auden’s “Lullaby,” which I think haunt anyone who ever attempted to contain Henry Smith for long. He may not have known the couplet, but he lived by it:

Lay your sleeping head, my love,

Human on my faithless arm.

Throughout this period Henry and I continued to study with Miss Adachi—as private students, meeting with her in her tiny room in a single-room-occupancy hotel in the East Thirties. Each week we presented her with one-page accounts of how we had spent the intervening days—reports that we wrote in hiragana, the syllabary used to write Japanese words phonetically, or kakakana, the system used to write foreign words phonetically. Neither Henry nor I ever mastered more than a handful of kanji, the elegant, multi-stroke characters that literate Japanese are able to read and write.

Edwin Reischauer, the most eminent of American authorities on East Asian history and culture, once called Japanese “the most cumbersome language system in widespread use in the world,” and the longer Henry and I studied with Miss Adachi, the more we came to appreciate the wisdom of his observation. We could chat about mundane events, but when it came to writing, we were never more than first-graders. And we both recognized that on the street in any Japanese city we were functional illiterates—unable to read street signs, bus schedules, and posted menus. (Japanese restaurateurs, well aware that all gaijin encounter this linguistic impediment, routinely display remarkably life-like wax and plastic replicas of their blue-plate specials in a shadow-box mounted alongside the entrance to their establishment… so that would-be patrons can simply point at an item in the box and say “I’ll have that.”)

It became obvious to both Henry and me that we had made as much progress as we were ever going to, short of a heroic push to learn the so-called kyo-ku kanji, the 1,026 characters that every Japanese child commits to memory while in elementary school. And yet we persisted, in large part because Miss Adachi ended each of our weekly sessions with the same exhortation: “Minna, ganbatte kudasai”—which means “Both of you, do your best.”

With the passage of time, I have forgotten most of the specifics of what Fumie Adachi taught Henry and me, but I still remember enough to say “Gochi-so sama deshita” to sushi chefs—who are, to a man, deeply appreciative of the compliment, which means “You are the bringer of the delicious food”… and is considerably more lavish praise than “Umai,” which means “Yum!” And of course I remember that furitsuke means “choreographer.”

In the end, my job at Newsweek Books and Henry’s ever-greater involvement in Solaris meant that neither of us had the time we needed to prepare our weekly essays for Miss Adachi, and rather than disappoint her by failing to ganbatte, we told her we needed to bid her a fond farewell. In parting she gave each of us a copy of Japanese Design Motifs, an illustrated encyclopedia of some 4,000 kimono crests, her country’s version of the heraldic orders set down in the Almanach de Gotha. I still have my copy, in which she is listed as the translator. The inscription is in hiragana.

Henry had an indisputable genius for spotting performers who had yet to be noticed by other impresarios—--a case in point being Michael Rivera. Henry gave Michael his first real job in the theatre, as a member of Solaris, the name Henry gave to his fledgling dance-theater company in a salute to a recently published science-fiction work with the same name. That novel, written by Stanislaw Lem and involving a protracted search for extra-terrestrial intelligence, had captured Henry’s imagination… for reasons I was never able to fathom, and he never bothered to explain.

With two year’s performance experience with Solaris as his only theatrical credit, Michael auditioned for a role in the 1980 revival of West Side Story. At that audition, Michael told Jerome Robbins, who both choreographed and directed the 1980 production, “You have to cast me. Because I am Puerto Rican, and because I grew up in the barrio in East Harlem.” Robbins concurred… and I was in the audience when Michael made his debut as Bernardo, leader of the Sharks and protective older brother of Maria, the Juliet in this reimagined, modern-day version of Romeo and Juliet.

When it came to musicians, Henry was, if anything., even more prescient. For his debut as artistic director and lead performer of Solaris, Henry somehow persuaded Tejii Ito to create an original score for the company. I have no idea what inducements Henry offered Tejii, who was fresh from writing the score to New York City Ballet’s “Watermill,” and who had previously won an Obie for the incidental music he wrote for a number of Off-Broadway plays. And then there was Guy Klucevsek, an utter unknown whose chosen instrument was… the accordion.

Guy would eventually transform the music world’s appreciation of the sort of sounds that the accordion can produce—and, in the process, revolutionize our understanding of its range and versatility. In the mid-1970s, however, the accordion was routinely dismissed as the mainstay of polka bands. To his considerable credit, Henry heard something in Guy’s early performances that no one else heard… and engaged him to create the score for several Solaris dance-theater pieces.

Like so many artistic directors before him, Henry could not manage to achieve a truly compelling, coherent, captivating blend of dance, theatre, commissioned music, and spoken text—and the appeal of the musical scores of his works, even when coupled with the talents of his troupe of performers, was insufficient to disguise this larger failing. The reviews of his efforts to attain that syncretism ranged from tepid (The Village Voice) to cruel (The New York Times).

Henry’s solution was to take Solaris to Paris, where he had always received adulatory notices whenever he performed at the Opéra with Carolyn Carlson. Here too Henry got lucky—because Parisian critics responded positively to the disjointed opacity of the very works that had irked and befuddled New York critics. To them, the lack of a theme and a through-line was the point, and one Parisian dance critic even went so far as to laud what he saw as the “bouffonneries shakespearienne” in the dance-theater piece that Henry showed in a shabby performance space in the city’s ancient Jewish quarter, Le Marais.

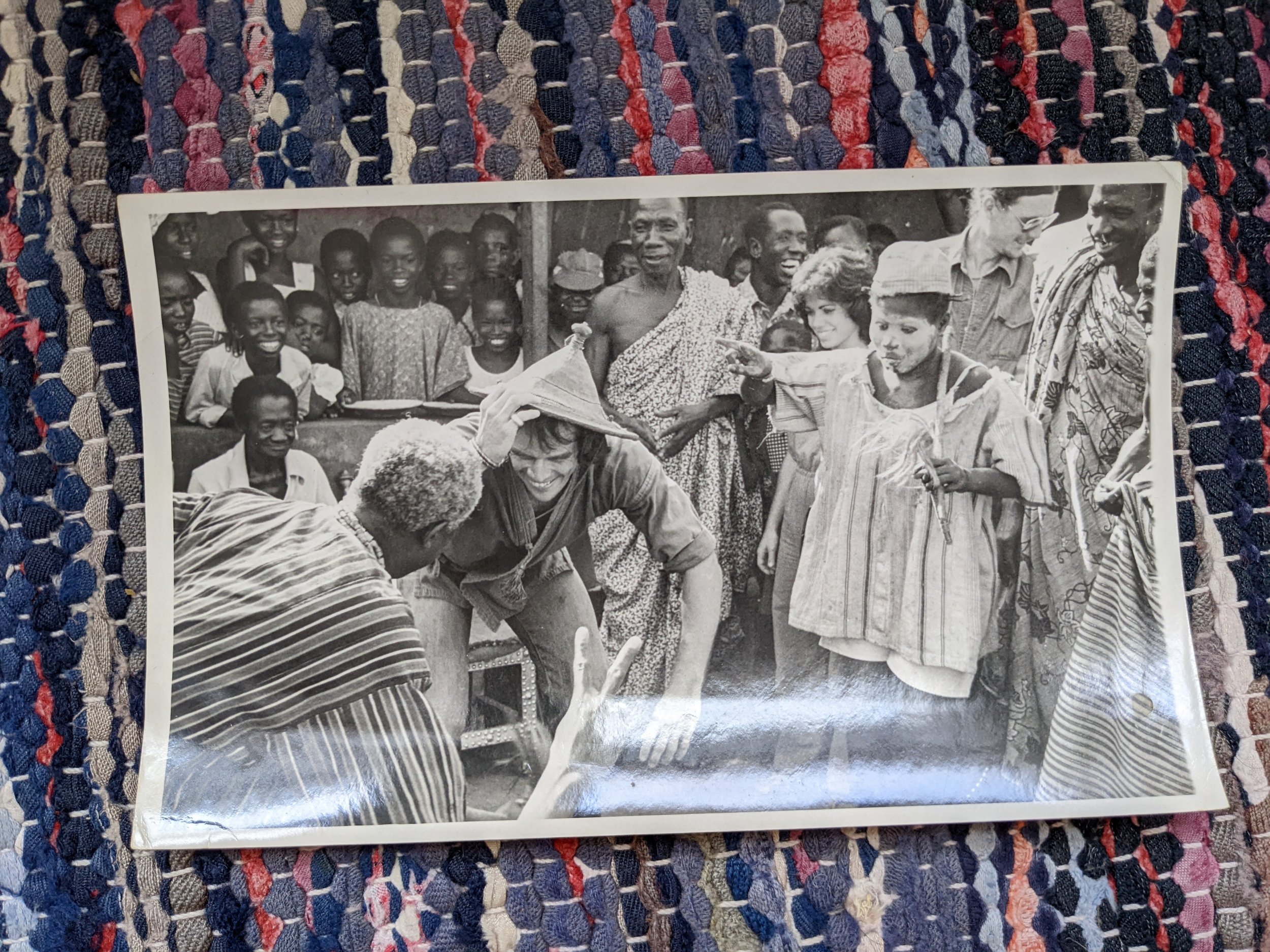

Restless by nature, easily bored, irked by the necessity of having to secure ever-larger grants to support his growing company, and thwarted by the first desultory reviews of his performing career, Henry simply reinvented Solaris—this time in a way that fused his two greatest enthusiasms, on-stage performing and ritualized combat. In yet another unlikely, unanticipated turn in a life characterized by unusual transitions, Henry found his way to the vast Sicangu Sioux reservation of Rosebud in South Dakota—the largest, and the poorest, county in the entire United States. I have absolutely no idea what drew Henry to South Dakota, but then I don’t know what inspired him to enroll in RADA or how he found his way to Paris and persuaded Caroline Carlson to add an undisciplined, untrained American to her company, which was otherwise made up entirely of beautifully schooled French dancers.

The line from “Lawrence of Arabia” that has become shorthand for explaining such inexplicable feats is “For some men, nothing is written.” That certainly is true of Henry Clay Smith III, who not only found his way to Rosebud but founded what he called the Solaris Lakota Project on the reservation—to revitalize the dance traditions of this once feared warrior tribe, now sunk into penury, alcoholism, and despair.

In a sense, this cross-cultural effort provided Henry with the home he had been searching for on two continents and across a range of disciplines. He taught the Sicangu Sioux aikido, and they taught him their Vision Dance. Henry and his troupe of a dozen Sioux dancers toured extensively, and their itinerary eventually brought them to New York City—where Henry finally got the New York Times review that his work deserved. That praise came from one of the paper’s dance critics, Jack Anderson, who wrote that the program performed by the Solaris Lakota Project was “at all times a serious tribute to an old, fascinating, once-endangered but now bravely surviving culture.”

All of this I would learn about second-hand, and after the fact, because by the late 1970s Henry had left New York in pursuit of what the Lakota call a vision quest—a solitary and single-minded search for life’s purpose. The Sicangu Sioux viewed this inner journey as the essential element of manhood, because its successful completion equipped a man with both spiritual power and social standing. Henry, who enjoyed high social standing by right of birth into a Main Line family that traced its descent from the Great Compromiser himself, found the society he was truly meant to be part of in a desolate, impoverished community on the American Great Plains.

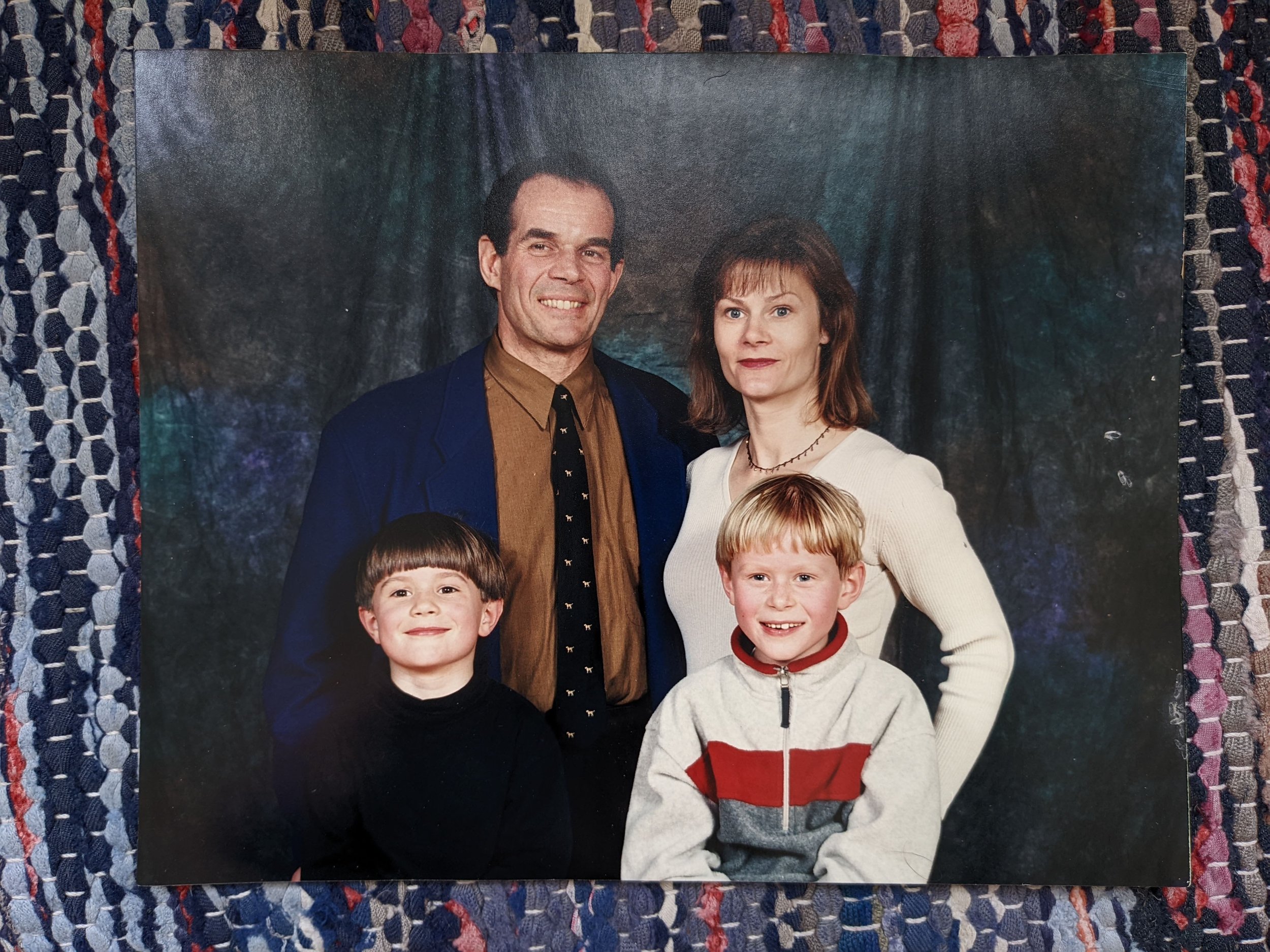

Henry was a modern Odysseus, and it is entirely appropriate, therefore, that he died a mythic hero’s death—while swimming in the Hellespont. (I wonder if anyone else remembers that his mother died in the same way: of sudden cardiac arrest, while swimming in the icy waters of the Atlantic off Cape May, New Jersey. Like her son, she died too young… and all alone in the dark depths.) Henry left two grown sons and an ex-wife.

Henry was also a modern Hamlet: aloof, enigmatic, impulsive, brooding, and—yes—melancholy. It is tempting to turn to the existential conundrum framed by Hamlets’ famed soliloquy—to be… or not to be—to explain Henry’s headlong rush toward something that would satisfy his need for resolution, something that would finally balance the yin and yang in his wildly contrary nature. But I have my own supposition, and it dates from those nights when he and I met in Miss Adachi’s tiny apartment. One of the few kanji that Henry and I learned from her is ki, which is written 気. Ki has many meanings in Japanese: heart, mind, spirit, feelings, and will. It is, moreover, the central precept of aikido… and as such it was, I have always been convinced, the real object of Henry’s lifelong vision quest.

It is, however, to my lifelong literary companion W.H. Auden, rather than to Shakespeare or the precepts of aikido, that I turn to for the proper words to memorialize Henry—specifically, these lines from W.H. Auden’s “Death’s Echo”:

The desires of the heart are as crooked as corkscrews,

Not to be born is the best for man;

The second-best is a formal order,

The dance’s pattern; dance while you can.

Dance, dance, for the figure is easy,

The tune is catching and will not stop;

Dance till the stars come down from the rafters;

Dance, dance, dance till you drop.